“A Symbol of Change: Quaker Oats and the ‘Aunt Jemima’ Brand Transformation”

The day after the decision became public, a great-grandson of the figure known as “Aunt Jemima” expressed strong opposition to the rebranding, believing that it would erase black history and suffering. He expressed his concerns, emphasizing that his family would bear the consequences of this decision. Larnell Evans Sr., a former Marine, felt a personal connection to the brand and considered it a part of his own history. He pointed out that after benefiting financially from slavery for a significant period, the company now had a responsibility to contribute to its abolition.

Evans also criticized the way white perspectives on slavery tend to dominate discussions about racism. He noted how businesses profit from depictions of enslavement and lamented that they were now erasing his great-grandmother’s history, a woman of non-white heritage, which was deeply painful to him. Quaker Oats announced that they would discontinue the brand indefinitely. The product’s logo featured Nancy Green, a black woman who had once been a slave but was described by Quaker Oats as a “storyteller, cook, and missionary worker” based on historical records.

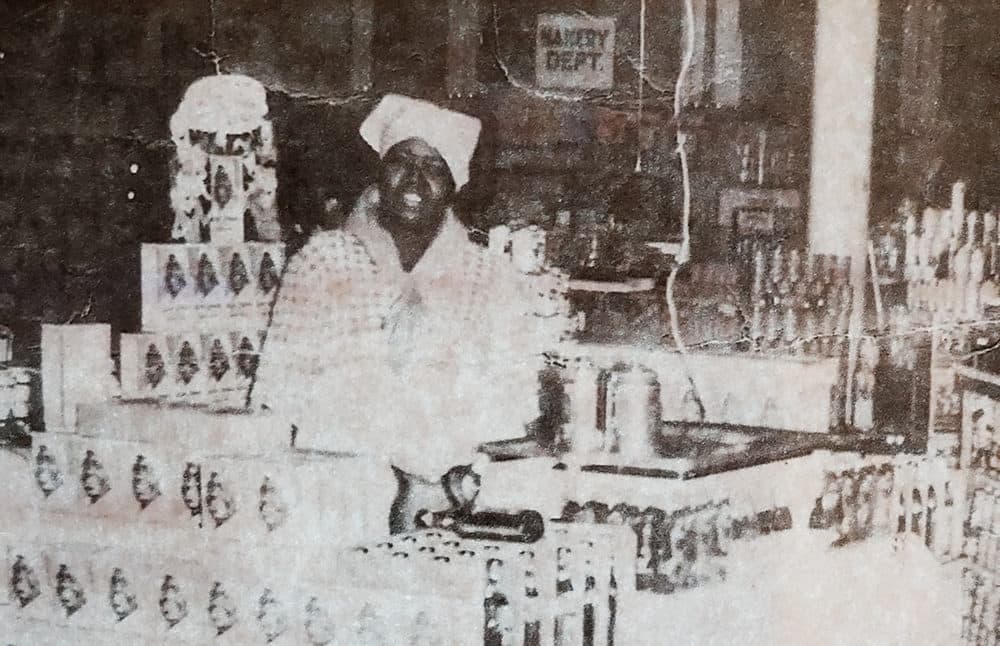

Green first adopted the “Aunt Jemima” persona in 1893 when she was contracted to serve pancakes at the Chicago World’s Fair. After the passing of Anna Short Harrington in 1923, a Quaker Oats representative bestowed the name “Aunt Jemima” upon her because of her pancake-serving role at the New York State Fair. Anna Short Harrington was buried under the name “Aunt Jemima,” as confirmed by Larnell Evans Sr., who claimed she was his great-grandmother. She began playing this role in 1935, having worked for Quaker Oats for two decades prior. As Aunt Jemima, she traveled across the United States and Canada, making pancakes for people.

Even after her emancipation from slavery, she continued caring for others, and Aunt Jemima became her professional identity. Evans, a black man, expressed his frustration that Quaker Oats had capitalized on a racial stereotype for profit and was now swiftly erasing it. He questioned how many white individuals grew up watching Aunt Jemima each morning while eating breakfast and how many white-owned companies profited immensely while providing little to the black community.

He asked whether these companies would simply ignore their past actions and offered no support. Evans was deeply troubled by the erasure of his family’s history and the ease with which Quaker Oats sought to remove the brand. He wondered if they would ever acknowledge the past and take responsibility for their actions.